What if I tell you, Christopher Columbus was not really an explorer.

Well, I am not asking you to reconsider a historical fact. Am I even qualified to talk about exploration, while real explorers do their wild and uncertain things, I sit on my lazy ass on a quiet and comfy chair in a corner of my house?

I am only interested in figuring why exploring is a fun pursuit. Exploration, not in the geographical territory per se, rather the “i want to explore more options before i decide” kind; exploring ideas and insights that change the way we think and transform us. Such a skill is a superpower, especially for knowledge workers.

Suppose, your boss asks you on a Friday evening to come up with a completely fresh approach or an idea by Monday morning (it could be about a product, sales pitch, presentation or a new venture)

And assume, that for some reason, google is down, internet connectivity is lost for your whole town during the weekend; however you have access to your bookshelf, your local library and can talk to your friends and colleagues in town.

How will you go about your research? Which book(s) would you look up ? Who amongst your peers would you go to?

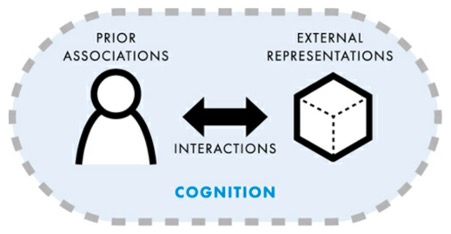

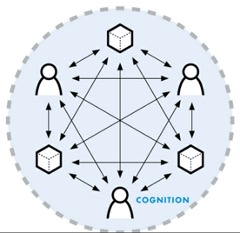

The idea of (re)search or exploration has been key to our thinking and thus, survival. Often we start with building on existing ideas, contacting known people. If we are lucky, we get useful points, connections between those, and once in a while, stumble upon something new – something we never knew it existed when we began the pursuit.

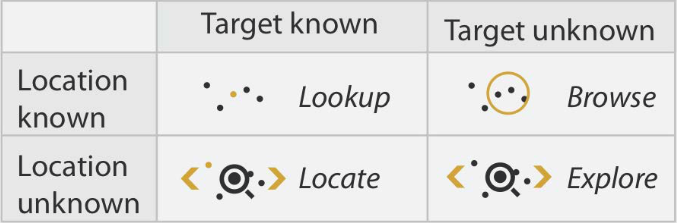

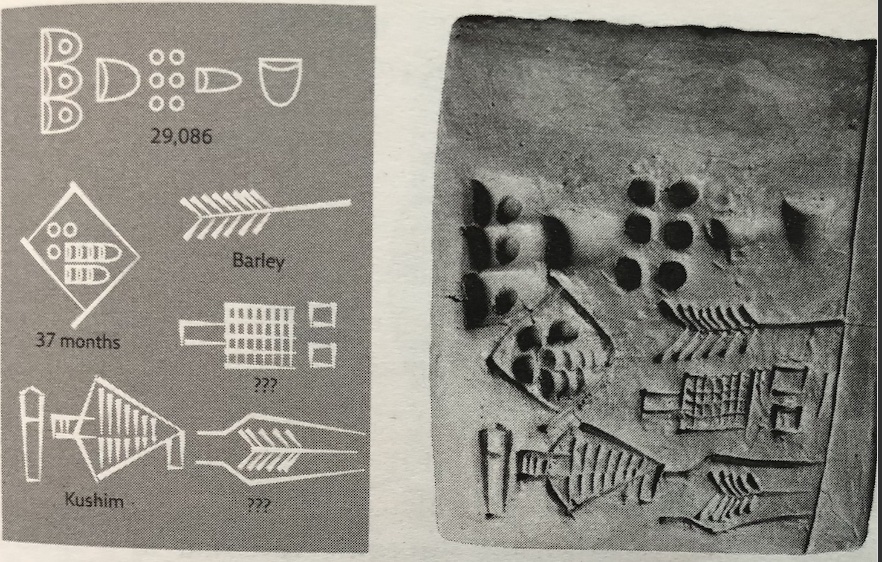

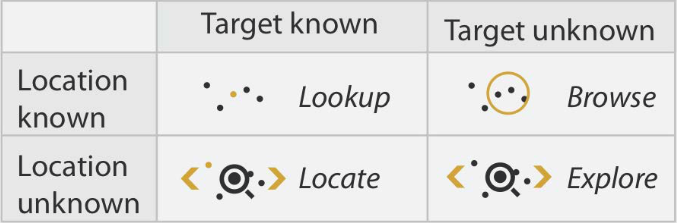

We all have been using the term, search so loosely. Tamara Munzner’s book on data visualisation has this matrix / table that made me think more clearly about the vagaries of search.

Lookup: most of the time, we know what we are looking for, and where to find it – like in your neighbourhood grocery store. You know what you are looking for, say milk. You remember where to go and fetch it. Easy and efficient. Why? So much organising has gone behind the scenes. I am not sure if it is even possible to organise and store information/ideas like a grocery shelf.

Browse: Sometimes we don’t know what we are looking for, but very clear about where to look. Example: in a library, you know there are enough gems buried inside those pages. All you need is time to browse a bit, and with some luck you might find something relevant. You might even stumble upon something new. This is fun – and efficient at the same time. Perhaps more exhilarating compared to fetching milk from your grocery store.

At the same time, a bit of organising is a pre-requisite to make this work. You should have accumulated related ideas or books in one location that you can go to. Or subscribed to Netflix, where the algorithm does the job for you – to keep you constantly stimulated.

Locate: this is like searching for your missing car keys. You know what you are searching for, but don’t know where it is. Also, this is where Columbus comes in. You see, in 1492 he set out “to find a direct water route west from Europe to Asia, but he never did”, landed instead on a different continent. He had his target/destination (Asia) known but the location (route) unknown. Thus, as per this matrix’s strict definition he is not an explorer, just a locator. And he failed at that too. There is even this blog that talks about how his GPS failed him big time. In the end, he returned empty-handed, frail, poor and without any recognition.

Sorry, I am taking a bit of creative liberty here. My point is: when we set out to find new ideas or insights, lot of time and energy is wasted in looking in the wrong direction. One of my simplest life-hacks is to ask for directions: the “right” colleague who might lead me to the “location” of many useful and interesting things. Because, most of the times, we don’t know what we don’t know.

Who Lucky: Jim Collins, the author of the book Great By Choice, has coined this phrase who lucky. “you get, not just luck in life, but “who” luck….And “who” luck is when you come across somebody who changes your trajectory or invests in you, bets on you, gives you guidance and key points.” (quote from Jeff Hilimire’s blog)

Finally, explore: The dictionary definition of explore: travel through an unfamiliar area in order to learn about it; inquire into a subject in detail. But as per the matrix above, explore is: we don’t know what exactly we are looking for, and we have no clue where to start searching. That sounds like pain. But imagine, if Columbus convinced his Spanish financiers that he is simply out on a voyage to discover something, no promises. He was better off in not setting any expectation, choosing to ride the vessel of uncertainty, with his mate named luck, and serendipity as his diet.

That would have been fun. The kind of exploration I am talking about.

However this pursuit is not trivial; not a reckless exercise, not without any structure. Here are a couple of useful techniques to explore:

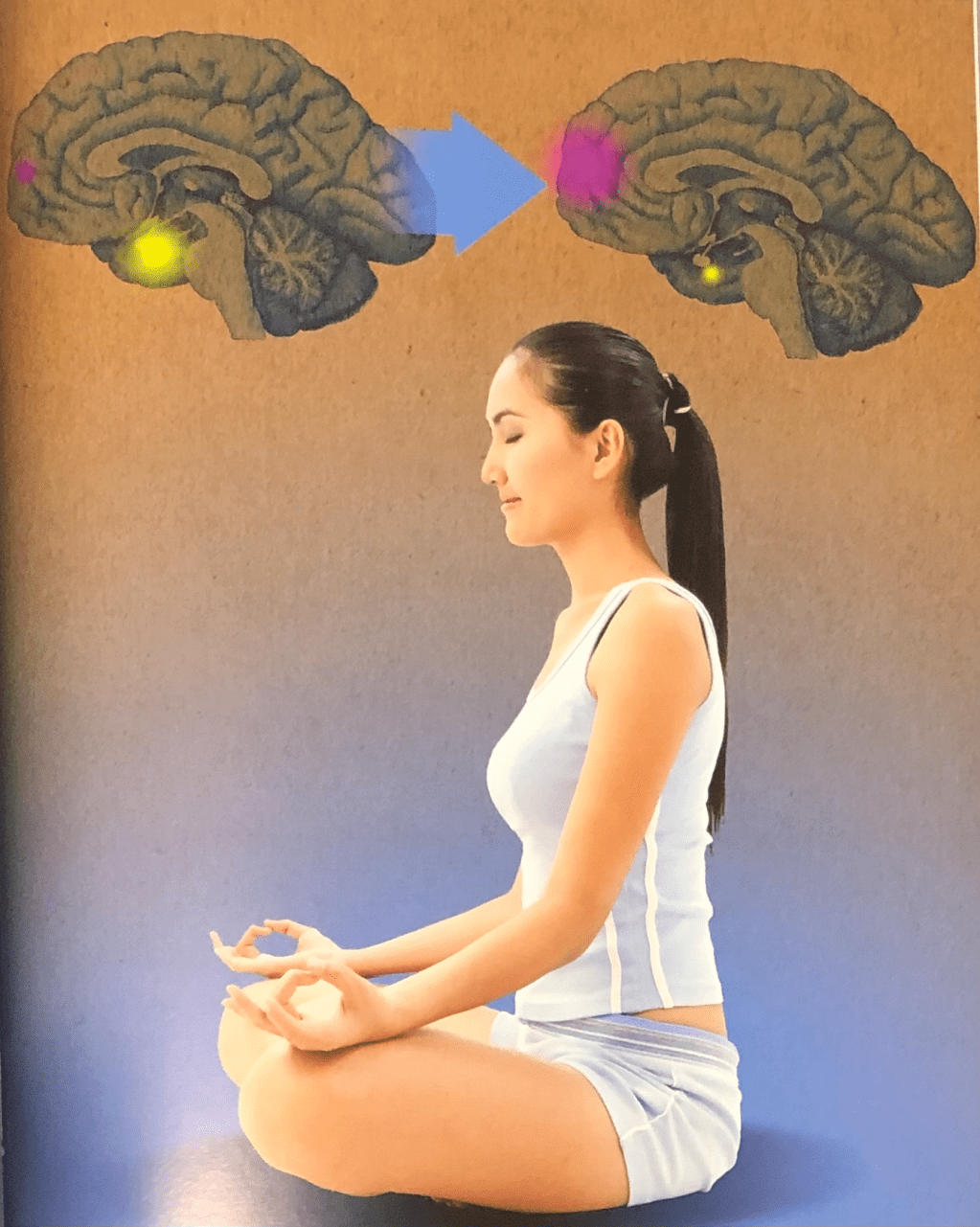

Visual thinking. For me, this is less of a technique, more of trying to be human. Once in a while, get off your device, walk outside and look up, locate the sky and browse the many stars. The change in visual stimulus is all you need sometimes. For a more earthly example, if I need an idea for presentation, I google the topic (eg. Technology Platform) and go “images”, and see the many illustrations. Something clicks in the mind, as this post illustrates how creative ideas emerge out of visual thinking.

Another useful one is Lateral Thinking, popularised by Edward de Bono. An example is Random Simulation. I use this when I need an opening word or a central theme for a speech or a blog. This is how it works: Choose a random number from 1 to 10, say 7. Open a random page of a random book; find the 7th word in the 7th sentence of that page. Reflecting on that word, its meaning, would evoke a feeling, trigger an idea, shape our thoughts.

(for this blog, that random word turned up to be destroy; no wonder I have been cynical about Columbus all through this piece)

The power of exploration is: only direction matters. Your curiosity is the direction. Go where that curiosity takes you, following what appeals to you, not worried about the number of steps taken, points collected, victories or failures; not anxious about reaching any destination.

In any case, as Yogi Berra said, if you don’t know where you are going, you have a good chance of not reaching there.

PS: This is the final of a 3-part blog post “How to Think Better”.

Part 1: “How to Think Better – Externalise”

Part 2: “Uncategorised” aka How to Think Better – Categorise