You see this lady with wild hair, walking all across the pavement ahead of you, deranged, rambling in pain, almost blocking you. You sense she is hurt, lost, lonely, and never in a million lives going to be a threat, yet you try ignoring her, avoid her trajectory, leaping towards the signal, and hope it turns green oh God, rush and jump into the pedestrian crossing, all the while astonished by your flight, your fright, and the sudden descent from self-congratulatory, priestly state of altruism into the hollow pit of apathy, worse, disgust.

Category: decision making

-

Ray of Reason

Fifteen years ago, I got promoted to manage a team of twelve. I saw myself as a young, aspirational and enthusiastic manager, guiding these young(er) bunch of men and women on a challenging journey to deliver a critical piece of software in a short period of time. Towards the end of the year, the software was subjected to thorough testing. Around the same time, I too got tested – a 360-degree feedback from my team on my performance.

The software performed well. I got thrashed. The team basically said, “We don’t like you(r style of managing)”.

I had a dilemma. Should I switch to being an individual contributor and play to my strengths in technology? Or should I learn from my mistakes, grow as a person and try to connect better with my team?

It will be several attempts, several years and many such corrective feedback cycles before I did better. On hindsight, I should have…

We need to think clearly in such situations. That is not easy.

These days, when I face a complex situation, I try a principle suggested by the billionaire, Ray Dalio. It is deceptively simple, but very effective. The method involves thinking through three questions and filling your answers across three columns on a piece of paper. Every time I fill those columns, I feel better. I feel I have understood, even if not conquered the complex territory I am navigating.

Here is the principle:

- Decide what you want

- Find out what is true

- Figure out what to do, based on 1 and 2.

I did warn you, it appears simple.

Ray Dalio has filled 592 pages of his book with many such principles derived from his life and work. Like a catch surprising the fisherman, this principle popped out of the first few pages, and I have only read fifty or so.

I stopped after the first catch, because I wanted to taste it first. As I began applying this principle, a key insight was how (1) and (2) are sometimes distinct. Even, mutually exclusive. The trick is to construct a bridge from columns 1 and 2, leading into 3.

If I had this clarity fifteen years ago, I would have identified my want as, “My team to deliver on the goals on time, on budget, with high quality, not getting burnt along the way, not getting micro-managed”.

I would have scribbled under the second column, “It is true, however, the team is under pressure; I am under the pump. Also true that the team has not been given a choice, not given a voice, and not clear on why we were doing what we were doing”.

If I had these three distinct columns, I would have not jumped to the actions. I would have learnt to be a bit more objective, a bit more sensible. Would have learnt to remove “I” from the equation and listen to what the team had to say regarding the goal pursuit.

On hindsight, I should have…

As I encounter this principle fifteen years late, I stop. “What is reality telling me? What are the constraints? What am I not thinking about?”

“What is true?”

I am still exploring this principle. Do let me know if this works for you.

-

A beautiful mindset

I have struggled with the word strategy all through my career. No, I haven’t struggled to make a plan or define a logical sequence of activities, but this whole strategising thing is something else that bothered me. How do you successfully get through to the other side of a challenging project to deliver, or an uncertain future for the product and team, or an unexpected change in career? Dealing with, and winning at these require more than grit or luck. Pure logic doesn’t help beyond a point. I have often heard from colleagues that life resembles a chess game, one to be mastered.

I am bad at chess.

My other problem is with the word, Art. There is an art for anything these days: “Art of speaking..”, “Art of writing…”, “Art of winning…” and of course, the ultimate “Art of living”. All my life, I was more into science and math, and I was particularly bad at art.

Bad at art, and worse at chess, I have no hope then.

I am good with reading books however, and to my pleasant surprise I landed on this book recently that carried both these words in its title: The Art of Strategy, A Game Theorist’s Guide to Success in Business and Life.

One of the authors of this book is a professor in the US but of Indian origin, which made me think: after all, wasn’t the Indian civilisation that gave birth to Chaturanga, the predecessor of the modern chess game? Even the famous epic Mahabharatha revolves around a game of dice gone wrong for the Pandavas. India is also the place of Chanakya the philosopher-guru who authored Artha-Shastra – a treatise similar to the more famous Art of War.

The definition of strategic thinking was very helpful: “the art of outdoing an adversary, knowing that the adversary is trying to do the same to you”, “art of convincing others, and even yourself, to do what you say.”, “art of putting yourself in others” shoes so as to predict and influence what they will do.

Out of the many strategies and approaches, the common theme for me was the element of surprise, as a winning ingredient in any strategy, especially dealing with bullies. The authors explain the best strategy to confront a powerful and intimidating bully at school, at work, or even a dictator: a sudden, visible, unexpected act of defiance by the collective.

The book as such is hard to finish, but there are some interesting parts not to be missed, especially the stories from world war, movie references (The Beautiful Mind, for example), and other real-life examples. The definitions of various game theory constructs eg. zero sum game, dominant strategy, Nash equilibrium etc. ) are well explained, until they loose you by going deep into the mathematics.

Yet, there is more to unpack from this book. It says at one point, “All of us are strategists. It is better to be a good one, than a bad one”.

That sounds to me a practical, if not a beautiful mindset.

-

Uncategorised

I bet you won’t continue reading this blog beyond a point, unless you find something new. Right at this moment, in your brain, a bunch of neurons are firing to figure out what this new is. I wonder if you got some ideas from the title, or some of the pictures below which your eyes cannot help scanning. I suspect you have mentally tagged this blog already – technical, boring, long. Interesting (hopefully).

Categories

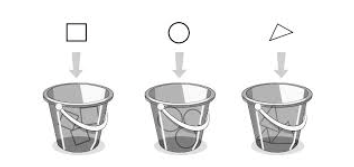

Our brain is wired to perform instant pattern matching and categorisation. Categories have strict boundaries which help us compare a “this” from a “that”.

This skill helped us survive as we made quick decisions under uncertainty – by differentiating between a branch of a tree and a snake; between a cold, warm or hot object. All thanks to the much evolved part of our brain: prefrontal cortex.

Now during the information (delu)age, we need this skill even more, as we distribute every bit of new information to various buckets. Worse, we do pattern matching even when the data doesn’t make any sense. Lets attempt this puzzle:

Kiki and Bouba are two nonsense words from a non-existing language. Can you suggest a match between the words and the two images below ?

Analogies

Cognitive scientist Douglas Hofstadter says categorisation and analogies are the way ALL thinking occurs in our brain. Watch him narrate this (15 minute into this hour long video).

We have so little control over this process. If our mind always compares and contrasts – as we see, hear, smell, touch and so on – several downsides occur. In a rush to make a quick judgement, we often make the wrong call.

Prejudice

I won’t talk about serious topics like racial stereotypes and unconscious bias in this blog. But I share a recent experience at the food court, when a seemingly innocent comment from the lady at the counter made me cringe a bit.

I sensed her watching me order rice and vegetarian curry with an additional order of papad. The many neurons in her brain didn’t have to perform heavy gymnastics to categorise me, as she suggested “so, you must be a south Indian?” I nodded. She said, feeling settled, “makes sense!”

She wasn’t wrong this time. No harm done. (maybe my moustache was a give-away). But not all of us are right when we carry out some lazy, sub-conscious thinking. When we assume.

Cognitive Bias

Daniel Kahneman is considered the father of behavioural economics. In his work, he underscores the fact that humans are not rational at all while making decisions. The nobel laureatte’s book Thinking Fast, Thinking Slow has made me more aware – if not smarter – as I learnt about various cognitive biases. A sample for you: Confirmation Bias – the tendency to search for or interpret information in a way that confirms one’s preconceptions. (eg. anti-vaccinators).

Rob Dobelli’s The Art of Thinking Clearly is another easy-read that I recommend.

Black Swan

Being aware of such biases helps us avoid an ontological shock.

In the 2nd century, a roman poet coined the term black swan describing an imaginary bird – since at that time, all known swans were white. That was until the 17th century, when Europeans landed in Australia, when they spotted a black swan.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb tells this story in his book The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. Note, the book is not about birds, but how we struggle with things that shock us – outliers.

I particularly loved the irony – these 17th century travellers declined to categorise that bird as a swan at all. In their mind, a swan had to be white.

Moral of the story: be aware of how we categorise. And, when we encounter a new idea that cannot be boxed onto an existing bucket, it deserves a new category on its own.

The Meditating Brain

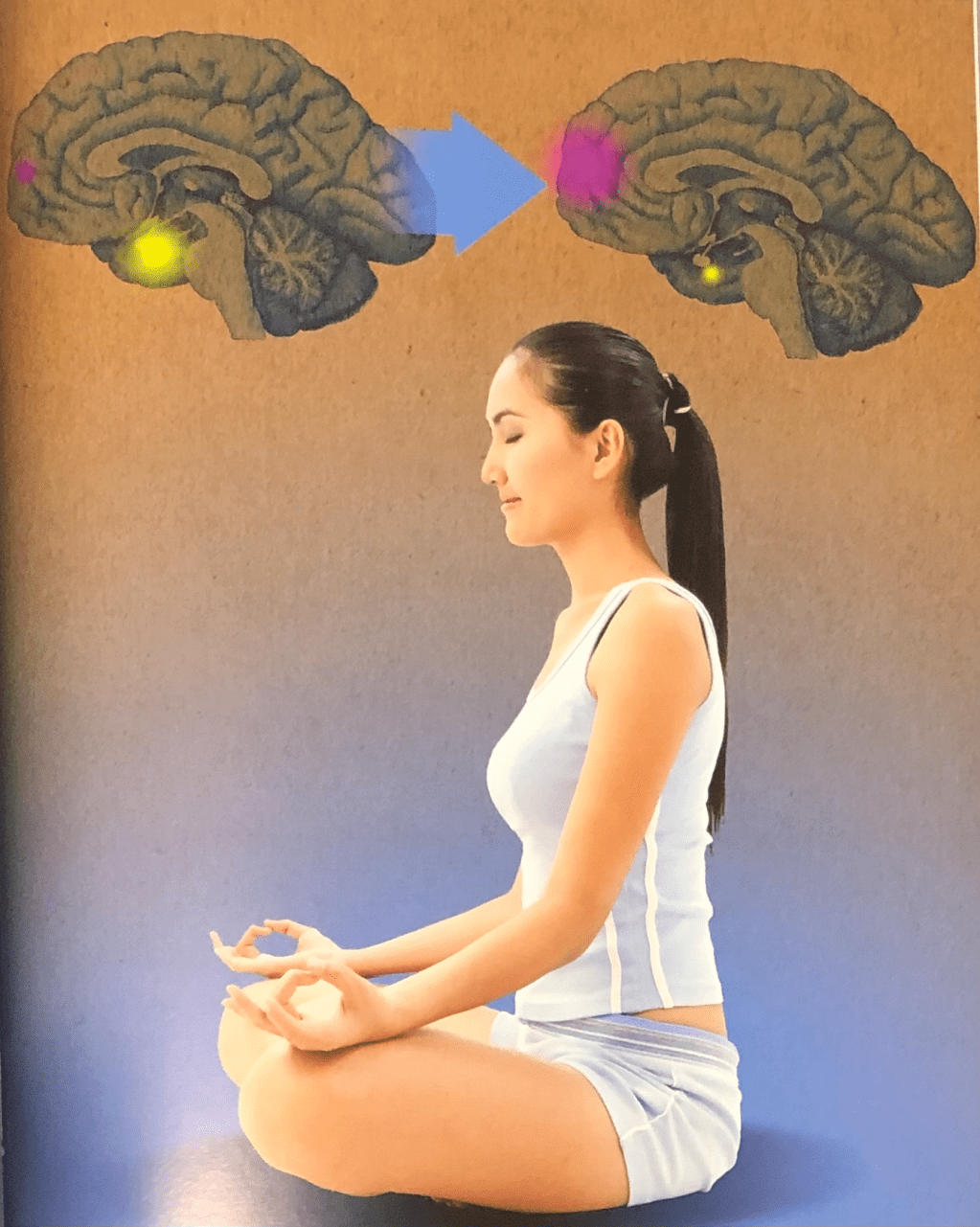

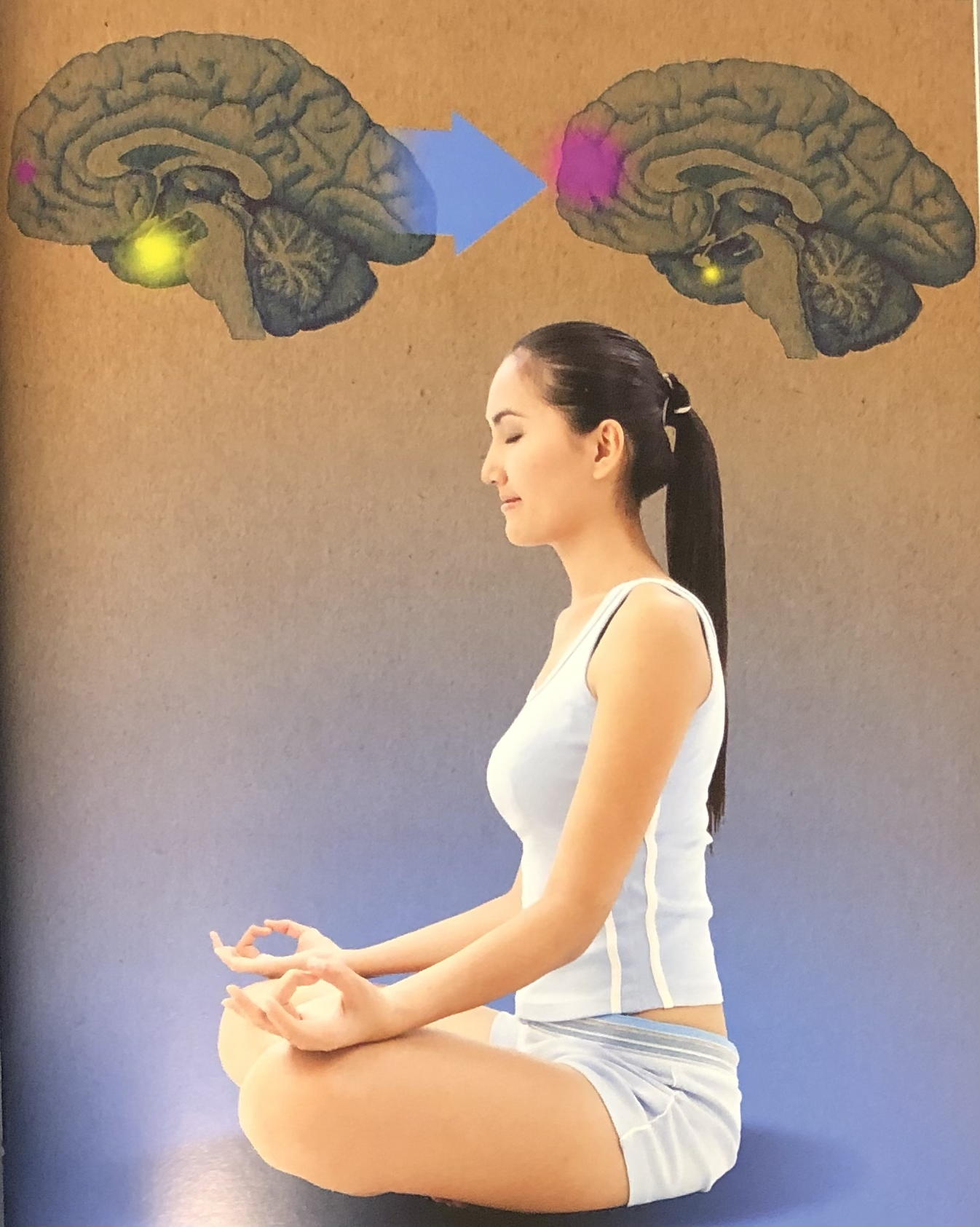

I mentioned earlier, how prefrontal cortex helps with categorisation. The picture-book “30-Second Brain”, edited by British professor Anil Seth, illustrates how meditation rewires our brain.

Just after 4 sessions of meditation, it is found that we use less of the primitive areas of the brain, activating the prefrontal cortext that helps us perform higher orders of cognitive functions and intelligence.

Kiki or Bouba ?

Did you associate the word kiki with the sharp edged object? You are like the 95% of participants of a famous experiment “Bouba/Kiki effect“.

We cannot help ourselves especially when we don’t realise we are making these associations. Are we stupid, are we wrong? Should we stop categorisation altogether ?

I finish with the simple and slightly modified words of a famous Henry Ford quote:

“Whether you think you should, or you think you should not – you are right.“

PS: This is the part 2 of a three-part blog post “How to Think Better”.

Check out Part 1: “How to Think Better – Externalise”

Part 3

to be written: “How to Think Better – Explore“ -

How to think better – Externalise

If I claim this blog will help you think better, you would wonder why is this guy talking about it. Even if you know me enough, the why part of the above question is valid.

I am no neuroscientist, nor a philosopher. I don’t even think clearly under stress. I still occasionally lose my car keys, and spend an annoyingly long time to make simple decisions. Worse, I keep changing my mind. What credentials do I have to write about thinking?

The only trophy I can flaunt is the collection of books in my home library, such as How to Think, The Art of Thinking Clearly, Thinking, Fast and Slow etc.

With so much thinking about thinking, when will i ever focus on “doing”, you might ask. Well, I want to share some life-hacks relating to thinking, that has worked for me.

Particularly, I want to write about three ideas in a three-part blog series. This one is about externalising our thinking process.

I will cover the last two ideas in subsequent blogs. Categorisation: to put various things you encounter in categories or buckets, and Exploration: to search for information and insights to make decisions. While none of these are my original ideas, I have begun applying some to good effect.

Externalisation – one way to look at this is: offloading stuff from inside your brain, onto a physical format in the external world. Eg. writing, drawing, talking; in fact, expressing of any kind – singing, moving, whatever.

Cognitive Load

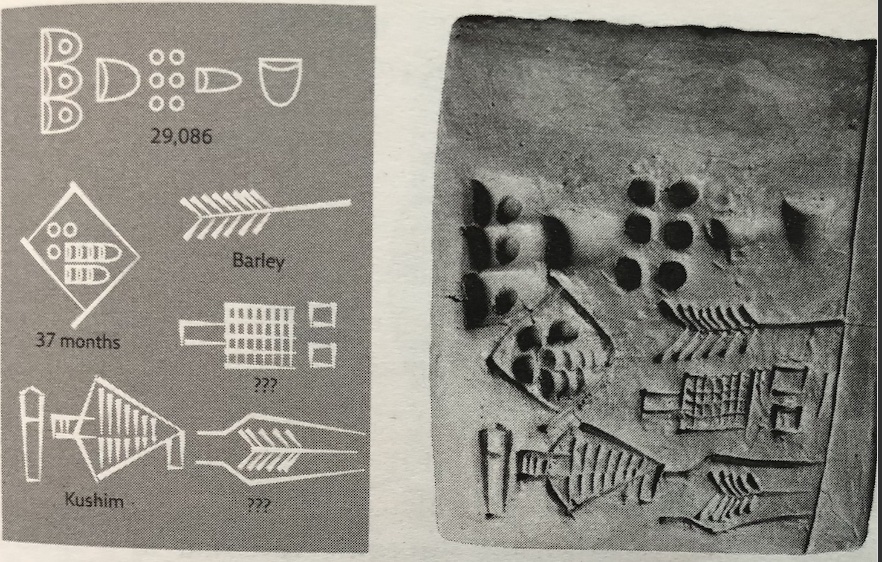

In my early thirties I realised I could no longer remember phone numbers from memory, and began writing them down. I thought it was a sign of getting old, but it appears, writing as a way to store information is a method followed since ancient times. Yuval Noah Harari writes about this in the bestseller, SAPIENS – that our evolution as humans may have depended on writing skill – shedding the cognitive load from our brain. Not the other way around. The book illustrates the Sumerian writing system from 3000 BC, as a method of storing information through material signs.

An interesting part of this story is about the first known “writer” in the world. Was he a poet, philosopher, story teller, king or a teacher? Nah. it was the boring accountant Kushim, the first recorded name of a human, ever.

I have written previously about how much of a game-changer it has been for me to write my thoughts, ideas and to-dos regularly. Sorry, I have harped on that enough – but please read along to get more convinced of why you should consider writing more.

Extended Mind

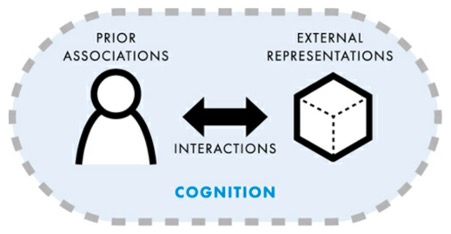

This idea of externalisation is more than just shedding something from our brains. It is about expanding the zone where cognition occurs: from the brain itself, to all places external to it, onto our body and even further outside. Stephen Anderson, in his delightful book “Figure it Out: Getting from information to Understanding“, explains the recent advances in neuroscience via a simple illustration of the Extended Mind.

When you have vague idea or a hunch about something, capture that instantly in a piece of paper, and look at it. Now, you have two things: your thought itself still lingering in your mind, and the external representation of that thought, staring at you as the text or drawing that you just created. This interaction in turn drives additional thoughts in your brain. Cognition powers through during such interactions.

Think and express, or express in order to think? The important aspect about the capture of our stream of consciousness (often containing incomplete thoughts) in an external format, is this: it is not as if we think clearly, and then express it. Expressing a vague thought – writing, talking, drawing whatever – actually is part of thinking itself.

In his research thesis, written as a brilliant book “Articulating a Thought“, that has a striking cover page, Eli Alshanetsky throws this paradox: when we express (eg. write down) what we think, we might feel unsure as to what we just expressed fully covered what we thought; on the other hand, without writing (or externalising of any kind), we wouldn’t even know what our thoughts were in the first place! Nevertheless, as Eli explains, the act of expressing our thoughts using language helps, because, language prolongs the thought; it completes the thought; and it specifies the thought.

Of all the known modes of expression, writing is found to be most energy-efficient way to express – and to preserve our thoughts. But it also happens to be the most difficult. George Orwell’s quote thus haunts us: “If people cannot write well, they cannot think well, and if they cannot think well, others will do their thinking for them.”

I didn’t write this blog after thinking through everything i was going to say. Infact, the act of writing – putting down my thinking into words and forming sentences – shaped my thinking about this topic. And every time I “looked” at the written text, it refined my own understanding of my own understanding.

In particular, writing using our hands, compared to say, typing, is proven to help our memory. In this paper, Kate Gladstone explains, handwriting is “far better at providing the necessary level of stimulation”, as it “activates a particular “network of cells within our brains: a “command center” called the Reticular Activating System (RAS)“, which is responsible for attention, alertness and motivation.”

Outsourcing our thinking to others

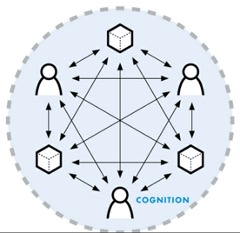

We are social animals. We express our thoughts and emotions with our partners, colleagues, friends and family. So, taking the idea of externalisation further, group thinking becomes very relevant when others are able to build on top of our thinking – as they express their interpretation of our ideas. This is more effective when we capture all of those thoughts and ideas from everyone in an externalised format that is visible to all (eg. writing in a white board).

I am part of a sales team and thus i often rely on others – experts in various lines of business within my company. Often we brainstorm ideas and decide together how to deal with challenges. This insight that I am not alone, and that i can delegate parts of my thinking to a huge bunch of experts, has been both an exciting and humbling one. I say this when asked if I know about a particular product or a technology. “I know that, because either I actually know that thing, or at least I know someone who knows that.”

Thanks to the internet, it has become super easy for us delegate this thinking to the whole world (eg. post a question in an online forum like quora, reditt or if you are braver, social media like twitter).

Walking helps thinking

I have often found that as i rake my brain to strategise, make decisions or look for new ideas, there is an irresistible urge in my body to jump out of my seat and walk. Walking is now an important part of my weekly activity. Especially after learning about the science on the correlation between walking and thinking. This Newyorker article explains well: article “Walking Helps Us Think”

“When we choose a path through a city or forest, our brain must survey the surrounding environment, construct a mental map of the world, settle on a way forward, and translate that plan into a series of footsteps. Likewise, writing forces the brain to review its own landscape, plot a course through that mental terrain, and transcribe the resulting trail of thoughts by guiding the hands.” “Walking organizes the world around us…Writing organises our thoughts”

I hope all this made sense. If not, please write back to me – I will really appreciate that. In the meantime, I will need more time to walk, think, and eventually write about the other two ideas as blogs.

Getting lost…

I have always been accused of an over-thinker and, in the recent years, I have been down many a rabbit hole: reading a lot about how to think better, thinking a lot about how to write well, and writing about all that comes to my mind.

I am actually not sure where this is going, but i enjoy getting lost in such thoughts. Last month, i went walking around the suburb on a newly laid trail into the woods along a beautiful water stream, while listening to a Tim Ferriss podcast. Thirty minutes later I found myself reaching on top of a small hill. I didn’t want to return home using the same path, and decided to try out a new route which turned out to be a dead-end – with barbwires and all that. Eventually, I had to use google-maps to get back home, which felt a bit embarrassing.

This unexpected detour though, triggered a random idea which helped untangle a mess – that was until then an unexpressed vague thought that was eating my mind that weekend.

Folks, get it out of your mind. It will set you free.

PS: Check out part 2: how to Categorise, and part 3: how to Explore

-

Press Any Key to Continue…

My boss put two questions in front of me recently, during the half-yearly review meeting. “What is the aspect of the job that gives you joy” – a nice, ego-boosting leading question that lead to a delightful conversation.

Her next question stumped me: “What is going to be your pet-project?”. “The one activity you could do on your own, during free time. Something you could come home to, when you have had an especially bad day”.

I drew a blank.

Homecoming

This question is significant today, as we perceive time, work and life very differently than just a few months ago. During the pre-COVID era(?), a knowledge worker like me would have separated work and life – at least physically, straddling across office and home each day. We used to talk about work-life balance. These days, there is not much of a discussion about balance. It’s all a blur at the moment.

A good blur, at least for me. I no longer need to get up worrying about ironing the shirt or to drive to work to be in time for the first meeting of the day. Time is aplenty. (My wife isn’t too excited though – having to come home each day only to see unwashed stained tea cups – one on the table, two lying on the floor and one missing).

Sorry, I digress. The point is, a different sort of homecoming is necessary to keep our sanity.

But, a pet-project ? You see, this phrase has two words that sound dangerous to the lazy-me: a pet needs maintenance, while a project needs diligent work towards completion.

Spend, Manage or Invest ?

On a serious note, what would i do with a bit of extra time ? Time = Money, they say. There was this crude poster i saw recently that compared how the poor, middle-class and rich deal with money:

– the ones who have less, SPEND.

– the ones who have moderate amount, MANAGE.

– the ones who have excess, INVEST.

How do i invest this little excess time? Typically i am bored, i look for interesting things in twitter (will write a blog one day, about the gems i discovered by following a few interesting people in twitter during this year), read a bit of philosophy/self-help books, watch movies (these days i’m into Turkish rom-coms). I also play a bit of amateur sports. However, i’m not serious about any of these things. I dabble.

Making Choices

To be serious about a pet-project, i have to generate a list of options, make a choice, invest time and energy, report on its progress, and show some result.

Choice! If i have a, b, c, and d as choices, it is mainly a question of what appeals to me the most. What if there is something outside this list that suits me better? How do i know what i don’t know ?

One would argue, it is not easy to make decisions even with clearly defined, discrete choices. The red or the blue pill, as Morpheus asks Neo in The Matrix.

When my daughter and my nephew were toddlers, they used to fight for the best toy. Once, faced with a red and a green plastic trumpet, the kids couldn’t come to an agreement who gets what. It ended like this: my girl grabbed both the trumpets and offered the guy to choose one of those. As soon as he decided on the green one, she knew exactly what she liked. She snatched that very green trumpet from the hands of the baffled boy, and threw the red one to him.

What to look for ?

Life is easier as a child. I am more indecisive than ever before and struggling to answer a simple question, with no clear list of options, nor a play-mate to try out a decision tree.

Perhaps this question should be framed as: what would you “work” on, given unlimited time & resources without any constraint whatsoever?

I looked around for some quick inspiration – maybe mentors could help? Or the so-called thought leaders – like Paul Graham – who says in his blog, What Doesn’t Seem Like Work, “The stranger your tastes seem to other people, the stronger evidence they probably are of what you should do.” He ends by asking, “What seems like work to other people that doesn’t seem like work to you?”

Unbounded and Unflattened

When i look back at my life so far, someone or something has always driven me somewhere. A rank to achieve, a course to finish, a job to get, a project to complete, a step to climb in the corporate ladder, a problem to solve for a customer, etc. Even when i indulged in creative pursuits, there had always been constraints or a boundary.

I am not sure how to wrest myself out of the set path – even if it is just for a hobby. Something different and random but not trivial; a pursuit that delivers pleasure but no expectation (i certainly don’t want additional responsibility and having to justify to anyone – including my nice and well-meaning manager, who surely will be reading this blog with a chuckle).

Anything, that amounts to something in the end.

Anything

This reminded me of a story about Compaq computers: In the 1980s, their customer support team had to spend a lot of time explaining first-time computer users, who called up to ask “Where is the Any key in my keyboard?”. The users were confused by the message in the computer monitor that instructed them to “Press Any Key to Continue”.

Where is my “any” key ?

-

To carry an oil lamp to buy a trash bin

The task was simple that evening, many years ago. We were four classmates beginning a new chapter in our lives: out of home, first job, new city, new apartment and the world to conquer. Two of us had to go get a trash bin for the house. The shop wasn’t far away and I wouldn’t complain anyway since this guy is quite a talker. He can explain the planets and cosmos while in the same breath turn philosophical or venture into the weird ways of the human mind. He once asked me, “think, what if you vanish one day and no one in this world remebered you”. We start walking the 300 metres to the bazaar. We see a small temple on the side of the road and he beings to wonder why religions exist in this world. I try to tell him we better hurry up before it rains.

The small road leads to the bigger road at the intersection. We only had to cross the signal to get to the home furnishing shop. But then we see this new music shop crop up on our left and we walk right into it. This guy had introduced the western pop genre to me. And as someone used to listening mainly south Indian film music, the name savage garden sounded more like a filthy place full of violent beasts than a music album (until I fell in love with the animal song). With a couple of new music cassettes (it was 1999; CDs will come much later) as we started walking back home, we both realized our folly. We started telling each other how stupid it felt to be forgetful and wandering away from the simplest task of buying a waste bin . We discussed the root causes while at the same time began fearing the ridicule from the other two waiting for us.

Why do we forget things and miss out on simple tasks or goals? Are we not serious enough? I am not even talking about life changing goals. Simple tasks that doesn’t need much thinking or planning. The office receptionist was laughing at me the other day, while making alternative arrangements as I had lost my id card and car park access card on consecutive days. I still don’t know where I kept them but I do recollect the thought stream in which I was drowned in during those days.

Life as a tourist:

Nassim Taleb has popularised the french word flâneur which loosely means wandering, idling or being explorative. It describes a tourist (who does not have a fixed itinerary) as opposed to a tour guide (who has mapped out a plan). Taleb explains the need to have a variety of options in life, career etc., so that you can take decisions opportunistically at every step, revising schedules or changing destinations. In the words of Yogi Berra “if you don’t know where you are going, you will end up somewhere else.” What if “somewhere else” turns to be more interesting and lucky?

I feel strange when people talk about a one-year goal, three-year vision, five-year target etc. I never thought I would be in an IT job even a year before joining my first job when I was only worried about getting good grades in the electronics degree. You have no clue where you going most of the time but you usually have some sense of direction. I used to be quite stressed out about not being able to control the outcomes and worry about slipping away from the “plan”. These days, I only keep a view on the high level goals and leave the steps to its own dynamics.

It feels like freedom as I go unstructured and unplanned once in a while, loosing myself into the world of new information, people, random corridor conversations, unexpected outcomes etc. It is OK since it feels more human and real. There is a parable about a guru teaching his disciple about methods of focussing the mind. He hands him a lamp brimming with oil that could spill if shaken even a tiny bit, and instructs him to walk around the temple. When the student succeeds at the daunting task, the guru asks him if he had a chance to marvel at the scenery: chirping of the birds in the tree, the smell of fresh flowers in the pond or the aesthetics of the temple. The student blinks as the guru points out the ultimate skill: the need to experience the world around as we focus on the task at hand.

But 19 years ago, as my friend and I were walking on a road to buy a trash bin, we didn’t have to carry an oil lamp. As we were talking, we soaked-in the sights, smells and the sounds and lost ourselves in them. The trash bin remained in the shop.

The other two roomies couldn’t control their laughter as we narrated our yet another failure to “get things done”. We told them how much we had been cursing at ourselves for being so absent-minded. Until when one of them wondered out loud, “when you guys started self-pitying, why didn’t it occur to you to just turn around, cross the road and walk into that bin shop?”

Please visit the Home Page to read my other blogs…

-

The (in)decision to help

I had always been fascinated by people who are able to throw themselves into rescuing someone in trouble, without indulging in a lot of thinking or analysing. Contrast that with people who either panic or act weird when faced with an ask to lend a helping hand. And some, in the attempt to help out end up complicating things. You wonder which category do I fall under.

Last month, the story of a “real life ‘Spider-Man’ saving a baby dangling from a balcony”broke the internet. An immigrant from Mali living in Paris did not blink once before “climbing up four storeys” to save the child. He is seen as a national hero in France and the President has offered him citizenship. Great news, but for some reason I felt something strange.

I knew why. Many years ago, I blinked when I could have helped a truck driver stuck in his seat after hitting a wall. It was not life-threatening and there was a already a crowd looking after him. It occurred at a village road I pass through in my motor bike ride to the Bangalore office. I was in a rush but surely, the heavens wouldn’t have fallen if I had stopped. Looking back now, I feel I could have at least offered to call someone or do something – I had a mobile phone at a time when it was still a luxury to own one.

Figured out later, not everyone at the office behaves that way. At least not my colleague, who demonstrated calmness (and sheer guts) under stress that helped save a life. The office bus that he was travelling in, hit a cyclist who was badly hurt. The driver ran away. The bus stood in the middle of the road causing a traffic jam, while the poor soul laid gravely close to the tyres. Our man didn’t think much before lifting the cyclist into the bus and taking the wheels himself to drive to the hospital.

This sense of guilt has never left me. I do help others but that’s not the point. Its about how I respond under pressure. Its about needing to possess both the instinct and intelligence to make a difference to a worsening situation. Though I did not encounter life-or-death incidents, even odd requests from strangers has left me stumped.

While waiting at the café outside the Brisbane Airport on my way back from an official trip, I had a young man approach me with a request to watch his bag while he makes a quick trip to the gents room. I declined bluntly even as I noticed the couple in the next table happily oblige. Later, my colleague assured me I made the right call, especially being outside an airport: Imagine an Indian caught with a ‘bag’ by the Australian aviation security personnel.

I did have a chance to redeem myself later that year. This too occurred in an airport and it involves my mobile phone which I failed to utilise many years ago. Waiting in the lounge (this time, inside the Canberra airport, having missed my flight) and being the only one present, I watched a lady and her kids approach me as they struggled with their heavy hand luggage. I was relieved when I figured I wasn’t asked to carry anything for them. She said her battery ran out and enquired if I would kindly offer my phone so that she could contact her husband waiting outside. I did not blink, think or analyse before graciously handing out my iPhone. She made a loud conversation in what I assumed was an African language and returned the phone expressing her gratitude.

As I was finishing that eventful day in Melbourne, I got a call from a number I didn’t recognise. I would discover soon later that my phone had knowledge of that number, when a male voice with think accent asked me, “Man, my wife called me in the morning from this number. And I waited in the airport for long but she hasn’t turned up yet. Where is she ?”